The First Hunger Striker

Marion Wallace-Dunlop had been an active campaigner for women’s suffrage from at least 1900 when she had joined the Central Society for Women’s Suffrage. When in 1905 the frustrated members of WSPU decided to become more militant in order to gain publicity for their cause this course of action appealed to her. Following a demonstration on June 30th 1908 Wallace-Dunlop was arrested and had her first taste of prison life which she found deeply affecting.

In 1909 she was again arrested, this time for wilfully damaging the stonework of the House of Commons by stamping it with a rubber stamp. Upon being found guilty of this crime she refused to pay the imposed fine and as a result was again sent to prison. Political prisoners such as the Fenians in the 1860s usually enjoyed much better conditions than usual, but the female suffrage campaigners were afforded no such luxury. Once Wallace-Dunlop was installed in Holloway prison she decided to protest this unjust treatment and embarked on a hunger strike, petitioning the prison governor:

“I claim the right recognized by all civilized nations that a person imprisoned for a political offence should have first-division treatment; and as a matter of principle, not only for my own sake but for the sake of others who may come after me, I am now refusing all food until this matter is settled to my satisfaction.”

This was the first recorded instance, but proved to set quite a precedent. After fasting for 91 hours the decision was taken to release her for fear she might starve. Although the decision to take this action was hers and hers alone, in proving successful her fellow suffrage campaigners realised they had a new weapon (Simkin, 2014). Marion Wallace-Dunlop ceased to be an active campaigner in 1911, but her contribution to the cause would not be forgotten and in 1928 she was one of the pallbearers at the funeral of Emmeline Pankhurst (Simkin, 2014).

Hunger strikes and force feeding

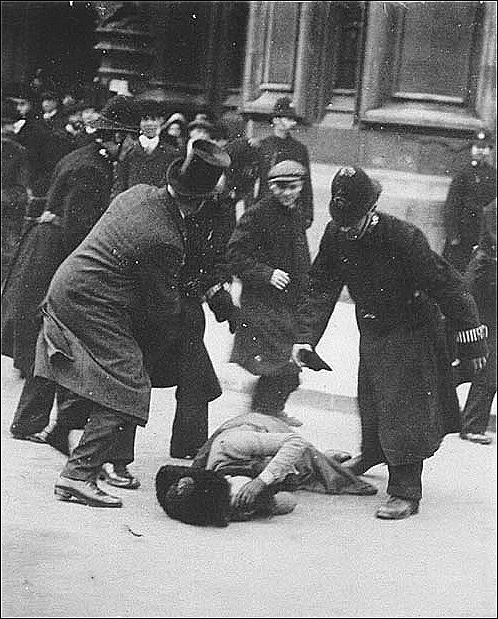

The suffragettes were quick to realise the value of going on hunger strike if and when they were imprisoned. The government could hardly let them die and become martyrs and so many to follow Marion Wallace-Dunlop’s example. At first this proved successful and many women were released until King Edward VII intervened. In a letter to the Home Secretary, Herbert Gladstone he questioned why this was the case when there were other ways to deal with the situation. Unwilling to release any more suffragette campaigners the prison authorities took drastic action and by September 1909 had adopted the policy of force feeding these prisoners. Many viewed this procedure as nothing short of torture and a public outcry ensued. In spite of this force feeding continued to take place right up the cease of suffragette militancy at the onset of the First World War (Turner, 2003). In some ways this played in to the suffragettes hands as the publicity given to this barbaric behaviour of a supposedly liberal government served to highlight the injustice of the women’s treatment. Such publicity was bought at a very high price though as the procedure was not only extremely painful but injurious to both body and spirit, possibly even fatal.

The suffragettes were quick to realise the value of going on hunger strike if and when they were imprisoned. The government could hardly let them die and become martyrs and so many to follow Marion Wallace-Dunlop’s example. At first this proved successful and many women were released until King Edward VII intervened. In a letter to the Home Secretary, Herbert Gladstone he questioned why this was the case when there were other ways to deal with the situation. Unwilling to release any more suffragette campaigners the prison authorities took drastic action and by September 1909 had adopted the policy of force feeding these prisoners. Many viewed this procedure as nothing short of torture and a public outcry ensued. In spite of this force feeding continued to take place right up the cease of suffragette militancy at the onset of the First World War (Turner, 2003). In some ways this played in to the suffragettes hands as the publicity given to this barbaric behaviour of a supposedly liberal government served to highlight the injustice of the women’s treatment. Such publicity was bought at a very high price though as the procedure was not only extremely painful but injurious to both body and spirit, possibly even fatal.

Lady Constance Lytton was one of many women who had to endure this ordeal and described it as follows:

“Two of the women (wardresses) took hold of my arms, one held my head and one my feet. One wardress helped to pour the food. The doctor leant on my knees as he stooped over my chest to get at my mouth. I shut my mouth and clenched my teeth. The sense of being overpowered by more force that I could possibly resist was complete, but I resisted nothing except with my mouth. The doctor offered me the choice of a wooden or steel gag; he explained that the steel gag would hurt and the wooden one would not, and he urged me not to force him to use the steel one. But I did not speak nor open my mouth, so after playing about for a moment or two with the wooden one he finally had recourse to the steel.

The pain of it was intense; he got the gag between my teeth, when he proceeded to turn it much more than necessary until my jaws were fastened wide apart, far more than they could go naturally. Then he put down my throat a tube, which seemed to me much too wide and was something like four feet long. The irritation of the tube was excessive. I choked the moment I touched my throat until it had gone down. Then the food was poured in quickly; it made me sick a few seconds after it was down and the action of the sickness made my body and legs double up, but the wardresses instantly pressed back my head and the doctor leant on my knees. The horror of it was more than I can describe.

I had been sick over my hair, all over the wall near my bed, and my clothes seemed saturated with vomit. The wardresses told me that they could not get a change (of clothes) as it was too late, the office was shut.” (historylearningsite.co.uk, 2014)

Her dentist was later to confirm the damage to her teeth and it is believed that a combination of this treatment, conditions in prison and the hunger striking itself led to a worsening of her pre-existing heart condition. Lady Lytton was just one of many women who experienced this with some such as Grace Roe and Kitty Marion being force fed more than 200 times (Purvis, 2009).

Eventually pressure from both the public and enraged MP’s combined with escalating embarrassment forced the Liberal government under the leadership of Herbert Asquith to introduce the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health) Act, commonly known as the Cat and Mouse Act due to the way it toyed with protesters as a cat does with it’s prey, releasing them only for them to be recaptured later once their health was restored. Many, including Christabel Pankhurst went on the run rather than face further torture in this fashion